“Home of the Brave,” by Bob Romano

Wild brown trout draw anglers to the West Branch of the Delaware below Cannonsville Dam. Photo: Bill Bullock

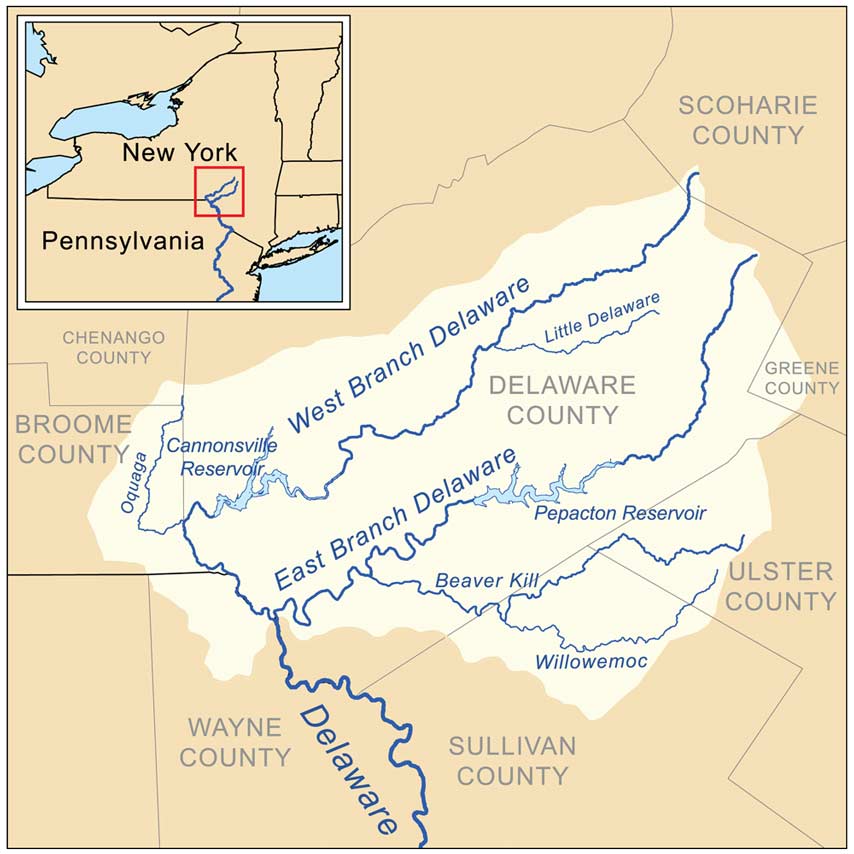

I haven’t been to the West Branch of the Delaware River since last fall. The No-Kill Section of the tailwater—populated by large and wily brown trout and located below a large dam in the mountains—is more than two hours north of where we live. I rarely make the drive until July, when Bonnie Brook is too low to fish. By then, sulfurs and blue-winged olives are hatching on the big river as cold water is being pumped from the bottom of the dam, forming ideal habitat for wild trout.

Last night, I pulled the cooler out of the attic, and stowed my larger net and 8-foot Leonard cane rod, the color of butter dripping off a cob of corn, behind the seat of the truck. In the morning, I stop at the bakery, walking out with a diet Snapple and a glazed bear-claw. I drive through the gap in the hills, which remained in shadow, and look down at the river.

The Journey

Each May, shad migrate up through this section of water, but by July, bass and pickerel have settled in, along with a few huge muskellunge. As the sun rises in my rearview mirror and I cross the bridge that spans the river, it isn’t shad or bass or pickerel, or even muskies on my mind, only trout—big, wild, 20-inch brown trout.

Map by Kmusser, used via CC BY-SA 3.0

The ride takes me into the mountains, through the bustling little town of Marshalls Creek, past a Boy Scout camp beside Resica Falls, and around the northeastern tip of Lake Wallenpaupack where folks from large cities cruise in motorboats while visiting their weekend cottages. Beyond the lake, mountain laurel and rhododendron sprawl down through scrub oak, red cedar, and white pine as Pennsylvania State forestland closes in from either side of the two-lane blacktop.

Farther north, I pass cabins with names like Lucky Boy, Itchy Pines, Memory Lane, and Classic. In the stillness of the early morning, miniature American flags hang limply from the windows and mailboxes of the little camps. Lights are on, as weekenders eat breakfast and make plans for the holiday.

Driving through the center of Hawley, I turn up the volume while listening to Jan and Dean. With the window open, I let the music carry me back to a time when there were “two girls for every boy.” The heat is already building, the radio announcer proclaiming it the perfect July Fourth weekend. Stopping for a light, I watch a young couple—holding hands and wearing shorts and sandals—cross in front of my truck. The boy wears a baseball cap similar to mine, but turned backward. The girl’s hair is long, and she sweeps a few strands from her face. As they enter a diner, she throws back her head and laughs at something the boy says.

On the radio, the Beach Boys are now singing harmonies as sweet as blackberry jam on morning toast. I pass through the larger town of Honesdale, turning right on Church Street where along either side of the wide avenue ivory steeples pierce the summer haze. When Brian Wilson’s falsetto succumbs to static, I turn the dial.

Project Healing Waters guides Veterans in-need to recovery through fly fishing, mentoring, and friendship.

Sacrifice

Coming upon the local public radio station, I catch the female commentator in mid-sentence, something about a young man, nineteen years of age, a lance corporal injured during his tour in Iraq. She’s explaining how a bomb exploded under the soldier’s Humvee. How he was one of the “lucky ones,” having been dragged out alive from the crumpled metal. Her voice fades as she describes how he is recuperating at Walter Reed Hospital from the loss of a leg.

I drive down into a valley where the landscape changes from forest to open fields and pastures. Dairy farms with white-clapboard homes and red barns replace vacation cottages and seasonal cabins. The signal is now barely audible as I pass through the rural landscape. I must strain to learn that the lance corporal grew up in the Midwest where he’d fallen from a deer stand, injuring his ribs the week before shipping out. Although the young hunter could have remained behind, he chose to accompany his buddies.

The voice of the soldier’s neighbor comes through as the static momentarily abates, “That was the kind of guy he was. The type of guy you could count on.”

Beyond the farms, I drive past a series of youth camps. With the window open, I hear the excited voices of children splashing in Indian Head Lake.

“He was always kidding around,” the young soldier’s sister sighs. “You couldn’t believe nothin’ he said.”

A few miles down the road, I enter the small village of Equinunk. At a stop sign beside a general store, I once again look down upon the river. It’s wide here, but this morning the current is hidden under early-morning haze. High above, the white tail feathers of an eagle flash as the large bird spirals downward on a thermal of air.

The Home Stretch

After the commentator concludes her report, a piano plays a few somber notes. Someone from the local affiliate predicts partly cloudy skies, temperatures in the high eighties, with isolated thunderstorms by late afternoon.

Not long after, I cross another bridge and drive over the New York State border into the town of Hancock, passing a McDonalds, its yellow arches draped in red, white, and blue bunting. Turning onto Route 17, I continue north through the softly contoured hills that rise above my destination.

Minutes later, I pull into the fishermen’s parking lot located beside the Deposit Men’s Club. After stretching my legs, I relieve myself beside a grassy berm. A few anglers work the riffles below me. Upriver, wisps of fog sweep over a long glide reminding me of tumbleweed blown down the main street of a western ghost town.

I tie a small Bead-head Pheasant-Tail Nymph to a short piece of tippet and knot it to the bend in the hook of a larger Prince Nymph. Casting the rig into the wide, slow-moving run, I let the two flies sink, waiting as they dead-drift back down past me. Slowly stripping back line, I step forward before casting again.

This type of fishing takes time. Time to think about whether that subtle nudge is one of the nymphs touching bottom or a brown trout about to expel the tiny fly before I’m able to set the hook.

Cast, drift, strip back line, step forward, cast again.

Time to think about a young soldier spending his summer in Walter Reed hospital.

Cast, drift, strip back line, step forward, cast again.

Time to think of a young hunter, sweating in the chill of a November morning as he strains to climb into a tree stand, his camouflaged fatigues masking a cold metal prosthesis.

Bob Romano’s latest book, River Flowers, is a collection of short stories about wild fish, the places they’re found, and the men and women who seek them out. For more information about his writing, visit his website, Forgotten Trout.