“Sometimes the Fish Don’t Bite,” by Jim Mize

Hellbenders live in some of our cleanest Appalachian rivers and certainly make interesting viewing. Photos: Jim Mize

That may seem an odd confession for someone who is both an angler and an outdoor writer, but sitting here with my left hand on a box of Girl Scout cookies, I feel the need to be truthful. I also crave a glass of milk.

But back to the fish, or lack of them. A falling barometer, high water, or any weather condition that tempts the Postal Service to stop delivering mail can cause the fish to clam up. At such times, continuing to flail the water with the same offerings simply makes your arm tired.

So, when the fish go on break, I’ve learned that it’s not a bad thing. Perhaps it’s just time to take a deep breath and look around.

Bottom Dwellers

For instance, I was recently standing knee-deep in a cold trout stream watching for any sign of bugs or fish. The bugs would suggest the fly I should use, and the fish would confirm they liked my choice. Seeing neither, I noticed something on the bottom of the stream.

About ten feet away, I could see a tail hanging out from beneath a large, flat rock on the creek bottom. Soon, the entire creature started crawling slowly my way. It looked like a prehistoric lizard. Approximately a foot long, it had a large flat head with a round mouth that went all the way around the front. Two beady eyes sat atop the head, and it’s feet had prominent toes.

The creature was a hellbender, the largest salamander in North America. Though we have a few in the area, I only see one or two each year, as they tend to be shy and I’m usually looking for fish and bugs. When this one finally saw me, it slowly turned toward deeper water and disappeared.

It reminded me of another hellbender I saw a couple years ago in the same stream. That one stayed closer to my feet for a while, as it was preoccupied by a small trout it was chomping on. The fish’s tail still protruded from the hellbender’s mouth. After watching for a few minutes, I eased out of the stream and left the hellbender to his meal.

Competition for trout can be fierce when a great blue heron is working the same pool.

Danger from Above

That hellbender was a reminder of the obstacles a trout might face in its quest to avoid being eaten. I often see a heron on the side of the stream, staring into a pool as if we are competing for the same fish. I once saw one catch a trout, flip it in the air, and gulp it down head-first faster than I could gasp. Apparently, herons don’t practice catch and release.

While I daydream on the water, I often see other birds of prey coasting overhead, as if scouting. On occasion, an osprey will fly along the stream low enough for a good look, and one farm pond I fish routinely hosts eagles each winter. I’m sure they catch fish when I’m not looking.

Besides thinking about the creatures that chase the same fish I chase, during the slow times, I investigate the foods that the fish chase. On a trout stream, that means flipping stones in shallow water.

Reading the Menu

All manner of aquatic insects—too many, in fact, for me to correctly identify them all—live on or underneath rocks. Mayflies, stoneflies, and caddisflies are the big groups. Mayfly and stonefly nymphs look nothing like the delicate winged insects they become. It’s a transformation as amazing as caterpillars becoming butterflies, just smaller.

Caddisfly cases more closely resemble grit and twigs, as the insects use these materials to build cases they live inside. Attached to the undersides of stones, these insect homes look as inanimate as the rock unless the caddis’s head and front legs protrude slightly.

Investigating further, I often flush a school of minnows from the shallows or a single, large sculpin that darts off to find another place to rest. Even the types of small fish in a stream tell you something about fly choice, since brown trout have a passion for a meaty meal.

Sometimes I become so distracted investigating the water around me that I look up only to realize that the fish have started to feed and insects are taking wing over the water. By then, I’m ready to engage them once again, armed with a bit more knowledge about what the fish eat and what eats them.

Life Lessons

Years ago, I interviewed a professional bass angler after a fishing seminar in which he shared his wisdom about a successful career on the tournament circuit. Wanting to ask a penetrating question to better understand the secrets of his craft, I thought about the situations that had stumped me over the years.

So, digging through my list of questions for just the right one, I asked him, “When it’s the middle of winter, cold outside, raining, and the bass seem to have lockjaw, what do you do?”

He thought for a second, obviously giving thought to many years on the water, and then replied, “I stay home and watch basketball.”

With all his years of experience, he had come to the same conclusion I have: Sometimes the fish just don’t bite. When that happens, there’s always something else to do, even if it’s watching hellbenders.

Maybe that’s what the fish are doing as well.

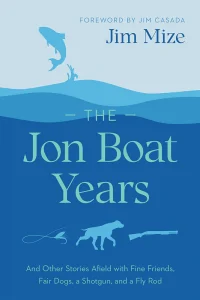

Jim Mize admits to occasionally catching no fish at all. Check out Jim’s new book, The Jon Boat Years, or buy autographed copies here.